|

I have been thinking a lot about what it means to be called, "colleague" in a denomination with a thorough credentialing process that may take a few years. Who really perceives students for who they really are, the gifts they bring, their growing edges? It can't actually always be the people we are called to serve because they have themselves to worry about and not the support of students, though this may incidentally arise. There are specific structures for student support, of course, but no one can actually force anyone to offer their common humanity. This is a gift of grace and friendship, with professional boundaries, of course.

1 Comment

They Look Like Walking Trees. <shrug> I see people. They look like walking trees. The image is three palm trees against a blue sky and a fleecy cloud. I see people. They look like walking trees. The image is three palm trees against a blue sky and a fleecy cloud. While being disabled has its challenges, one of the hidden gifts it offers is the opportunity to see how often people act in compassion. Sometimes people show their compassion in tiny, lovely ways. Not too long ago, I stopped at a coffee shop to get a latte, breve, three raw sugars. It had a lid on it, but as I held the coffee in one hand and drove my scooter away from the counter, the coffee splashed on me. There was a tiny, hot puddle on the arc between my thumb and forefinger. Another coffee shop customer crossed my path: brown corduroy blazer, blue tie, round, gold-rimmed glasses, and he stopped. I thought he was going to offer to carry my drink. Instead, he took a napkin and wiped my hand. He reminded me of the difference between sympathy and empathy. He reminded me that acting from empathy can lead to lived compassion. Of course I can feel sorrow over someone else’s suffering. This is something like a quick review of it, like trying to read a billboard while your bus rushes by on the highway. Blurry. There’s a story about something like this in the Christian Scripture. Jesus arrived at Bethsaida in the middle of a tough conversation with Their followers. “Do you still not get it?” Jesus asked. Then some people came. “Jesus, please,” they said, “our friend can’t see. Can you heal his eyes?” Jesus went with the man outside of town. Then he spit in the man’s eyes. This is fair because a lot of times when we are called to act in compassion it is not neat and sanitized. It’s just a human situation, with humans in it. I’ve spilled coffee. I’ve made a mistake. I encounter someone struggling with poverty or illness or addiction. God doesn’t ask me to be perfect, but God does ask me to hold still long enough to be of use, to have the spit applied, to be the spit. To have my hand wiped off. “Do you see anything?” Jesus asked. The man said, “I see men. They look like walking trees.” I think this part of the story is funny, mostly because it brings on what my friend Thea calls, “the laughter of recognition”. I am that person sometimes. I am covered in the miracle of humanity, surrounded by miracles, each of whom has a universe of life and experience inside them. And sometimes all I see is trees. I sum up their story in one line or less, the annoying one, the aloof one, the homeless one. To actually feel the experience of another, to respond and act from that place is connecting more closely. It’s thinking of how life feels for another person. This allows them to be someone with whom we relate for who they really are. One way to read healing stories in Scripture goes beyond disability being bad and healing being good. Rather, we ask of the story, “Where does transformation happen?” So Jesus laid hands on his eyes again. The man looked hard and realized that he had recovered perfect sight, saw everything in bright, twenty-twenty focus. Jesus sent him straight home, telling him, “Don’t enter the village.” The man realized his eyes were fine. Maybe the blurry moment was practice in really focusing. Maybe the transformation happened not in the person’s eyes, but in his heart, as he was able to consider, as are we, how it is that we really define and consider the people around us. Compassion calls us to consider them as human, which is to say, as particular miracles. We can respond and act in that way. #1000Speak For more information: http://yvonnespence.com/all/he-is-worthy-of-compassion/ Today I had a conversation about ableist language that went something like this:

January is the busiest year of the month for me. This is why I haven't blogged more. Generally, the plan is to blog on Fridays! Friday! I am having a study day: [dis]ability + theology. It turns out that old forms of theology bear explicit rejection. Our forms of theology and preaching tend to reinforce ableism in a few specific ways. These are from Nancy Eisland's The Disabled God.

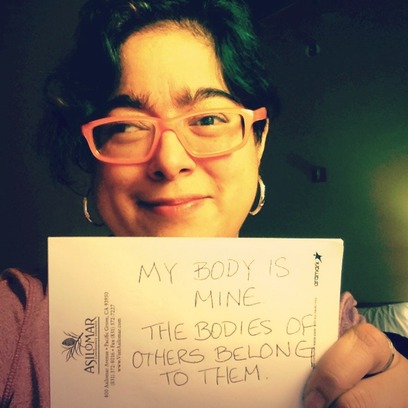

Friends, siblings in faith, ministers, I am going to skip to the end. Who you know yourself to be and your ability to live justly is implicated when the way you perform faith does not take these three issues into account. I am not oppressed by my body. I am, at times, oppressed by the decision people in community make to discount the importance of my body as a container and home. I am, at other times, oppressed by the acting out of people's values: that my body is too much trouble to include in community, that they are too uncomfortable with my differing ability to envision that I can meaningfully participate with them. I am not oppressed by my neurological differences. Rather, I am freed by them, since they are part of the mind that constitutes exactly who I am. I am not oppressed by having cerebral palsy. It is interesting, and funny, and allows me to grow into my best self by offering me over and over the opportunities to embrace my own non-typical humanity. I will never be normal. In this, there is beauty, freedom, and liberation. I am not oppressed by arriving at my own humanity, one of the many infinite ways of being human. I am oppressed when, somehow, using a scooter makes it difficult for others to access and connect with my humanity. You may not come after me and make meaning of my body or of my disability. Stop trying to do that. My body is mine. The meaning of my body is mine. Make meaning of your own body. Free your own self. I have a tradition of posting a poem or meditation for Christmas. Here is this year's.

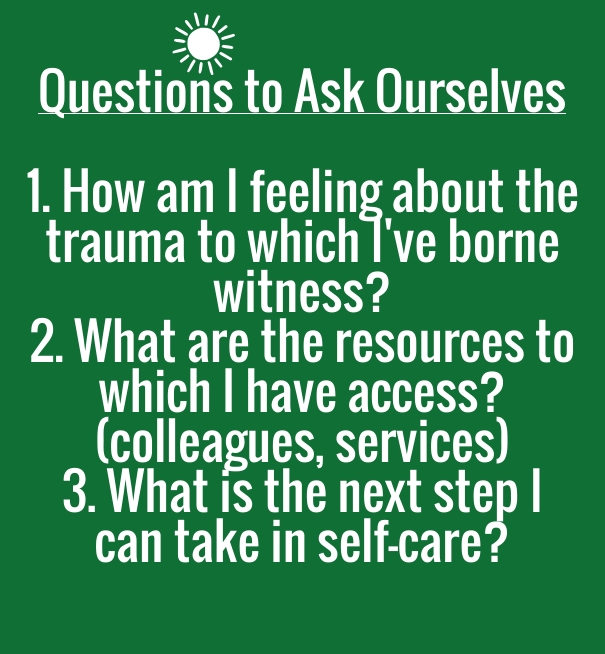

I try to bless you with words on Christmas. I try to bless you with words on Christmas. I try to look beneath the wrapping and ribbon And remember the humble wood and straw. I try to think of how it is that a baby marked By a star held for a while the hope of God. And the Love, infinite and fathomless of the Creator. But this year, these deaths, This persistent anti-blackness does not allow For blithe silence, punch and cookies, while Black people die in the streets. Rachel weeping for her children is this. For they are each, Michael, Tamir, Antonio, Raynisha, Trayvon- Mary at the foot of the cross is their mother. And white privilege is the wise men who say: We have come to the right place at the right time! I try to bless you with words on Christmas. The holiest words I have are their names.  You know, where it ends usually depends on where you start. "What It's Like", Everlast Do you know the backstory of Paul Revere's ride or the Liberty Bell or the first American flag? As we sift through collected American history, we find that maybe not all of it actually happened. George Washington probably didn't chop down the cherry tree or throw a silver dollar across the Potomac River. There's more. Beneath many of the cultural values people hold in the United States is a single myth: the myth of redemptive violence, or the idea that order [good] must triumph over chaos [evil] by means of violence. Thus, violence is good because it leads to greater good. It is the myth that powers patriarchy, imperialism, and racism. Let's examine racism through the lens of redemptive violence. Specifically, I want to consider how anti-blackness is fueled by the idea that violence is for someone's own good. But let's put it simply. In nearly every hero story in comic books and movies, one thing happens: good guys kill bad guys. That sounds familiar, right? Superman has Lex Luthor. The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles have The Foot. When they destroy their enemies, they are righteous because their enemies represent unalloyed evil. They are taking a shortcut to justice. There is no lengthy court procedure of due process. The failure of due process is one of the things that has been bothering me for months, as I consider the murders of black people at the hands of police and the ensuing no-indictments. But through the lens of redemptive suffering, I can see that these people who take black lives with impunity are acting on their belief that they are the good guys; to hold this belief and act on it to the point of murder, they must simultaneously hold that black people are bad and that destroying them is not a bad act because, unless they are destroyed chaos will triumph. That's sick and evil, under any definition I can conceive. Within the context of a cut-and-dried hero myth, the gunfighters or vigilantes serve a specific purpose: they break the law, "betray[ing] a profound distrust of democratic institutions and on the reliance on human intelligence and civic responsibility that are basic to democratic hope. It regards the general public as passive and unwise, incapable of discerning evil and making a rational response." -Walter Wink in Engaging the Powers: Discernment and Resistance in a World of Domination So while they assert that their actions are essential to the guarding of liberty, they are, in fact, villainizing black people to make them a foil of the hero myth and to allow themselves to continue to concentrate power among themselves. So what does it mean? It's a clear explanation to me of why our society looks the way it looks. What to do about it may vary from person to person, but we must begin by looking at the way we embrace violence and the way we are complicit in projecting that [anti-blackness] on black people. You can approach the problem of anti-black racism from lots of angles. Given your gifts and interests, pick something. Do it. Do it with all your heart. Challenge the idea that violence can solve anything. It's really important. It's really important that you do it now.  Or Self-Care, Part 1 Richard Harrison and Marvin Westwood from the University of British Columbia propose that the very empathy that we use to offer care to others can help to protect us from vicarious trauma. I am going to write a series of reflections on their article as it relates to pastoral care. It’s been a hard week, all around, for people who offer pastoral care to others. I’ve been wondering about my own spiritual landscape and thinking of what I need to continue to do the work of ministry in a sustainable way. Having a holiday with family was delightful, and yet, I know I’ll begin the next week with a memorial service. How do I do the work without letting it do me in? Vicarious trauma is not burnout, but actual injury. One reason I am giving this serious thought is that I’ve heard at least one statistic that Unitarian Universalist ministers spend, on the average, five years in ministry. I find this staggering, since a Master of Divinity degree, the educational preparation required for ministry, takes three years. One of the things that is important to me is considering the impact of vicarious trauma. Vicarious trauma is a complex group of, “cumulative transformative effects [. . . ] resulting from empathic engagement with [people].” The cumulative effect can be damaging on people who offer care and can result in, “physical, emotional, and cognitive symptoms” the same as those of people in their care.” Talk about taking your work home with you! In ministry, we talk openly about letting the suffering of others break our hearts. I think, at times, we are assuming that our hearts with naturally mend themselves. In fact, ministers or intern ministers can engage in nine different kinds of protective practices that will allow them to be resilient when it comes to the trauma of others or vicarious trauma. I’ll be writing on these separately and considering what they mean for me as a seminarian and intern minister. "Countering professional isolation" Addressing isolation can help us deal with the impact of trauma. This is interesting because Unitarian Universalist congregations arise and thrive in community. But their caregiver, then, the minister works, in some ways, alone. Though she may have a staff, there is some grief and trauma that she can only process with another clergy person. This immediately makes me think of UUMA resources, but I can call to mind at the same time colleagues who are too burdened with work to come to collegial meetings. That’s a real thing. The knowledge of what’s at stake urges me to both prioritize time with colleagues and to have a back-up plan for when its not possible. I have a cohort for my ministry internship. I wonder what would allow us to make part of the culture that we talk openly about countering isolation. I wonder if there can be more specific support for consideration of pastoral care case studies. We participate in supervision as a cohort and as individual interns, but I wonder if further consideration of “supervision as relational healing” is something we can build into the work that we do together. In order to allow that to occur, I would have to be able to be open about the symptoms and effects of vicarious trauma on me as I see them. If I were discussing with others, I might hear how they deal with the effects of vicarious trauma. For everyone, the shame of vicarious trauma would lessen. For me, this means that while it is important to gather with colleagues, the nature of the conversations that we have can make more difference if it addresses the deep difficulties that arise in giving pastoral care. I wonder if those conversations are possible in current structures. I wonder what else can be created to foster them. For the entire article, please see, as follows: Richard L. Harrison and Marvin J. Westwood, “Preventing Vicarious Traumatization of Mental Health Therapists: Identifying Protective Practices,” Psychotherapy, Theory, Research, Practice, Training 42 (2009); 203-219.  Bobby Seale Bobby Seale With reverence and sorrow, we remember the death of Michael Brown. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. On Saturday, August 9, 2014, Michael Brown was shot by an officer of the Ferguson Police Department in Ferguson, Missouri. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. The media gives us conflicting stories. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. We are not distracted by misinformation. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. Misinformation encourages us to put our frustration and sadness somewhere outside of ourselves, outside of these walls. On the police, on the dead young man, on the system. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. As a community, we reflect on the thread that connects the actions of an armed police officer with our own. We examine our snap judgments. We challenge the times we have remained silent while another suffered. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. We recognize that in order to challenge a system that is built to maintain racism, we must contemplate the effects of our everyday actions. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. We do not look away from the things that are hard to see. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. When justice eludes us We bear witness. We take courage. We bear witness. We extend love. We bear witness. |

AuthorCandidate for Unitarian Universalist ministry. Archives

December 2015

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed