|

0 Comments

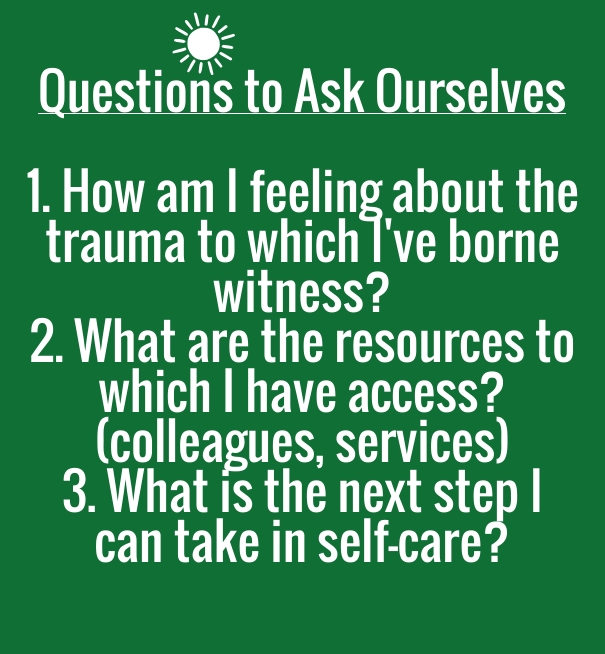

Or Self-Care, Part 1 Richard Harrison and Marvin Westwood from the University of British Columbia propose that the very empathy that we use to offer care to others can help to protect us from vicarious trauma. I am going to write a series of reflections on their article as it relates to pastoral care. It’s been a hard week, all around, for people who offer pastoral care to others. I’ve been wondering about my own spiritual landscape and thinking of what I need to continue to do the work of ministry in a sustainable way. Having a holiday with family was delightful, and yet, I know I’ll begin the next week with a memorial service. How do I do the work without letting it do me in? Vicarious trauma is not burnout, but actual injury. One reason I am giving this serious thought is that I’ve heard at least one statistic that Unitarian Universalist ministers spend, on the average, five years in ministry. I find this staggering, since a Master of Divinity degree, the educational preparation required for ministry, takes three years. One of the things that is important to me is considering the impact of vicarious trauma. Vicarious trauma is a complex group of, “cumulative transformative effects [. . . ] resulting from empathic engagement with [people].” The cumulative effect can be damaging on people who offer care and can result in, “physical, emotional, and cognitive symptoms” the same as those of people in their care.” Talk about taking your work home with you! In ministry, we talk openly about letting the suffering of others break our hearts. I think, at times, we are assuming that our hearts with naturally mend themselves. In fact, ministers or intern ministers can engage in nine different kinds of protective practices that will allow them to be resilient when it comes to the trauma of others or vicarious trauma. I’ll be writing on these separately and considering what they mean for me as a seminarian and intern minister. "Countering professional isolation" Addressing isolation can help us deal with the impact of trauma. This is interesting because Unitarian Universalist congregations arise and thrive in community. But their caregiver, then, the minister works, in some ways, alone. Though she may have a staff, there is some grief and trauma that she can only process with another clergy person. This immediately makes me think of UUMA resources, but I can call to mind at the same time colleagues who are too burdened with work to come to collegial meetings. That’s a real thing. The knowledge of what’s at stake urges me to both prioritize time with colleagues and to have a back-up plan for when its not possible. I have a cohort for my ministry internship. I wonder what would allow us to make part of the culture that we talk openly about countering isolation. I wonder if there can be more specific support for consideration of pastoral care case studies. We participate in supervision as a cohort and as individual interns, but I wonder if further consideration of “supervision as relational healing” is something we can build into the work that we do together. In order to allow that to occur, I would have to be able to be open about the symptoms and effects of vicarious trauma on me as I see them. If I were discussing with others, I might hear how they deal with the effects of vicarious trauma. For everyone, the shame of vicarious trauma would lessen. For me, this means that while it is important to gather with colleagues, the nature of the conversations that we have can make more difference if it addresses the deep difficulties that arise in giving pastoral care. I wonder if those conversations are possible in current structures. I wonder what else can be created to foster them. For the entire article, please see, as follows: Richard L. Harrison and Marvin J. Westwood, “Preventing Vicarious Traumatization of Mental Health Therapists: Identifying Protective Practices,” Psychotherapy, Theory, Research, Practice, Training 42 (2009); 203-219.  Bobby Seale Bobby Seale With reverence and sorrow, we remember the death of Michael Brown. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. On Saturday, August 9, 2014, Michael Brown was shot by an officer of the Ferguson Police Department in Ferguson, Missouri. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. The media gives us conflicting stories. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. We are not distracted by misinformation. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. Misinformation encourages us to put our frustration and sadness somewhere outside of ourselves, outside of these walls. On the police, on the dead young man, on the system. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. As a community, we reflect on the thread that connects the actions of an armed police officer with our own. We examine our snap judgments. We challenge the times we have remained silent while another suffered. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. We recognize that in order to challenge a system that is built to maintain racism, we must contemplate the effects of our everyday actions. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. We do not look away from the things that are hard to see. We know black lives matter. We bear witness. When justice eludes us We bear witness. We take courage. We bear witness. We extend love. We bear witness. Theresa loves you. Theresa likes lots of stuff. Theresa doesn't like lots of other stuff.11/21/2014  I love glitter. And we'll get to that, but I am going to begin with the idea that when someone articulates a standard for the way someone should dress, they are articulating more than just an item on a shopping list (ie, buy black pencil skirt.) They are defining a context in which a person can belong or participate. This is OK most of the time. One of the times its not OK is when there are reasons that the standard doesn't really fit the person. I just read an article on things you shouldn't wear after thirty. I was expecting to see polka dots. I saw instead, among other things, hoop earrings. Listen, this is a case in which the standard is too generic. I wear hoop earrings because I am Latina. The article said specifically that you have to be in high school to wear those. That rule might fit someone else. For me, hoop earrings are a cultural expression and an expression of my personal power. Let's talk about power. Does the way I dress telegraph power? Recently, a colleague told me that I am one of the most colorful dressers he's ever been around. I loved that. My most important commitment lately is to be available to Life, Dressing colorfully is about that for me, about expressing some of the affection I have for the world in the beauty of the colors I wear. I guess it's not a linear thing: I wear color because I am in love with God, the world, and myself and I'm not afraid to show it. But there's a lot at stake. Francesca Stavrakopolou, in reference to academia, phrased it this way, "The unspoken dress codes of academia are simply a reflection of the wider policing of women's bodies of women's bodies in other professional contexts in western society. No matter what their occupation, women are still frequently frequently held to account for their appearance, rather than only their expertise and experience." Is this something that happens in ministry, where power is mostly the mantle of ministerial authority as we each take it up? I believe it does. There is a white cis-male conception of authority which a woman's body does not fit. I think about the way having a disabled body further decenters me from that white cis-male conception, because in that original mental, emotional picture of what a minister is, he's never disabled, never walks with a cane or drives a scooter. I worry about the physical location of my body on the chancel in relation to the pulpit when I'm preaching. (It's too tall to use from my scooter.) I worry about what being seated telegraphs about my power. These are real things that people parse when they decide whether I have the power to do the work and bring the message that I hold. I am over thirty. I am going to wear two kinds of glitter eyeshadow in the pulpit. Not enough for you to think we are at a club, but even from a distance, I need you to locate my face and look at my eyes. I'll be the one up front, talking to you about building Beloved Community and living your values. I might wear a flowing skirt. I'm going to sit in my scooter and preach to you. You have the skills to deal with it; what's at stake is the growing of your spiritual self and your own understanding of your humanity. I know it might take getting used to. Thankfully, we're in this together. Theresa loves you. |

AuthorCandidate for Unitarian Universalist ministry. Archives

December 2015

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed